This is the fourth installment on this topic.

To read from the beginning please go to posts beginning 9/20/12.

The Causeway Boulevard exit of I-10 is just a few miles west of the 17th Street Canal which serves as the western boundary of Orleans Parish and the City of New Orleans.

The canal is typical of the numerous drainage canals that furnish paths for water away from the low-lying areas of the city into Lake Pontchartrain, via intermediate pumping stations which move the water upwards to the level of its release into the lake.

As one of the primary canals, this one is enclosed on its east and west sides by earthen and concrete levees to contain the excess water being pumped toward the lake and to prevent flooding during major rain events.

Waters from the Gulf of Mexico and Lake Borgne that had surged in with Katrina from the east, along with flood water that had found its way way from the city into the canals, all pushed backwards uncontrollably through the canal breaks, away from the lake and into the city bowl. During this process of water accumulating from the lake on the north, into uptown on the south, and into downtown, the French Quarter, the 9th Ward, Central City, New Orleans East and St. Bernard Parish, all to the east, access into the city via I-10, and most other entrances had become impassable.

Virtually the entire city was accessible only by boat.

From the hub-bub of emergency vehicles and helicopters at the Causeway exit, in order to reach the next “staging area”, we

moved south on Causeway Blvd Lake Pontchartrain Causeway

Bridge connecting the city and its older suburbs to the new, burgeoning developments north of the lake in St. Tammany and Tangipahoa Parishes.

On this day though, the normally bustling roadway was deserted, like the Interstate had been. However, travel was significantly more treacherous with downed power lines, power poles, pieces of buildings and other unrecognizable debris requiring heightened senses and extra caution. Occasionally alternating between the main road and the adjacent frontage road, we were able to weave through the mess and found our way to Airline Drive. There we turned to the west, fully 180 degrees off of the path that would have taken us into New Orleans when roads are passable.

During this 15 minute trek, none of us was aware of the extent of the flooding and the blocked roads into the city. Following the instructions from those who appeared to be in authority at the Causeway exit, we continued, but began to question where we would ultimately end up. We continued west for only a mile or so and came upon a large accumulation of parked vehicles with trailered boats in the roadway in front of Sam’s Club warehouse store. No one appeared to be in charge and no plan of action was evident, so we followed the pattern of those who had arrived before us and made a U-turn on Airline Drive. It was of minor sub-conscious comfort that we were at least pointing back in the direction of the flooded downtown area.

The vehicles, mostly pickup trucks, and their boats lined up in formation, three abreast and 10 or 12 deep on Airline Drive, apparently waiting on instructions, authorization or something. Then we waited some more. Some of us wandered around the "staging area" hoping to find some guidance.

On this day though, the normally bustling roadway was deserted, like the Interstate had been. However, travel was significantly more treacherous with downed power lines, power poles, pieces of buildings and other unrecognizable debris requiring heightened senses and extra caution. Occasionally alternating between the main road and the adjacent frontage road, we were able to weave through the mess and found our way to Airline Drive. There we turned to the west, fully 180 degrees off of the path that would have taken us into New Orleans when roads are passable.

During this 15 minute trek, none of us was aware of the extent of the flooding and the blocked roads into the city. Following the instructions from those who appeared to be in authority at the Causeway exit, we continued, but began to question where we would ultimately end up. We continued west for only a mile or so and came upon a large accumulation of parked vehicles with trailered boats in the roadway in front of Sam’s Club warehouse store. No one appeared to be in charge and no plan of action was evident, so we followed the pattern of those who had arrived before us and made a U-turn on Airline Drive. It was of minor sub-conscious comfort that we were at least pointing back in the direction of the flooded downtown area.

The vehicles, mostly pickup trucks, and their boats lined up in formation, three abreast and 10 or 12 deep on Airline Drive, apparently waiting on instructions, authorization or something. Then we waited some more. Some of us wandered around the "staging area" hoping to find some guidance.

Ronny and Sara had roamed over into the Sam's Club parking area.Finding no clear authority or evidence of a specific plan, they returned with two cans of spray paint and no clear instructions on what to do with it. We would discover later, like much of America, that flooded and damaged homes were marked with a pattern of numbers identifying buildings that had been searched, marking the locations of victims and quantifying the number of those whose remains would have to be gathered.

Ronny and Sara had roamed over into the Sam's Club parking area.Finding no clear authority or evidence of a specific plan, they returned with two cans of spray paint and no clear instructions on what to do with it. We would discover later, like much of America, that flooded and damaged homes were marked with a pattern of numbers identifying buildings that had been searched, marking the locations of victims and quantifying the number of those whose remains would have to be gathered.

(X-code, an iconic graphic applied by search-and-rescue teams in 2005 post-Katrina New Orleans.)

Our cans were placed on the seat of one of our trucks to be rolled and tumbled around the cab

for the next few days, never to be opened.

After an hour or so, the movement of other vehicles in groups out of the formation had resulted in our group being at or near the front. We saw no one giving instructions and received no information, but when the other vehicles moved, we followed. The sub-conscious relief provided earlier by our change of direction to the east, reversed itself when the beginnings of our new caravan made an immediate U-turn back to the west. We moved for a mile or two into the late afternoon sun, a group of about 45 boats, destination unknown. Directed by an unknown and unseen leader, we turned left onto Clearview Parkway, another major north south thoroughfare. Curious, but uninformed about the plan of action, I began to realize that we were coming upon the Huey P. Long Bridge that crosses the Mississippi River.

The bridge was built in the 30's under the auspices of its namesake, a wildly popular governor and United States Senator. Appealing to the Depression era masses, he had become a serious contender for the U. S. Presidency proclaiming the Populist standard of "Every Man A King". Known as The Kingfish, he was killed in his prime by multiple gunshot wounds received in the lobby of the 24-story state capitol building that he had built as a monument to himself. The bridge was opened 3 months later.

As a college student in the 1970's, I could visit the capitol building where the errant bullets from the event remained for public viewing, imbedded in the marble walls surrounding the first floor elevators. One problem is that it is still the subject of debate over coffee or cocktails, whether the bullet or bullets that caused the death of The Kingfish a day or two after the shooting, came from the gun of Dr. Carl Weiss Jr., the alleged assassin, or from the guns of law enforcement wildly firing to subdue him.

To this day, the state remains dotted with engineering accomplishments like the capitol building, constructed for the benefit of, and as a constant reminder to the citizens (and voters) of the state of the love that Huey P. Long bore for them. The bridge over the Mighty Mississippi, which we were now approaching was an

engineering marvel in its day, as the first crossing of the Mississippi

River in this area where the river is its widest.

Upon the long line of trucks and boats squeezing into the narrow entrance ramp of the bridge, it became evident that it was intended to accommodate smaller vehicles during a slower time. Crossing the bridge, without the usual congestion of high-speed traffic, it was hard to imagine how two lanes of speeding traffic could be squeezed onto the shoulder-less roadway between the railings separating traffic from the river on the outside and the train tressel on the bridge's interior, when the city was fully operational. We each held our breath as an emergency vehicle screamed us out of our quiet focus and anticipation and flew by us, forcing our steady line to hug the right railing as we cautiously descended the narrow bridge.

Our route did not indicate that we

were going into New Orleans,

|

This location, and another similar scene we would encounter the following day on the elevated portion of I-10 above

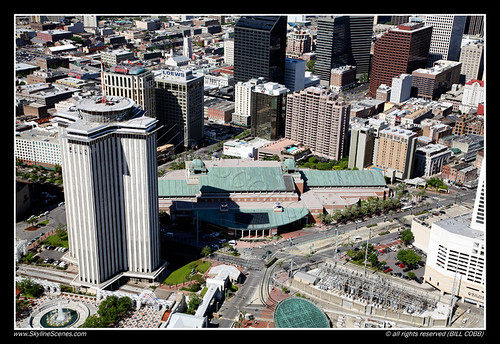

At the bottom of the exit ramp, we found ourselves peering directly into the face of the Ernest

At the bottom of the exit ramp, we found ourselves peering directly into the face of the Ernest

At the foot of Poydras Street, at the end of Convention Center Boulevard , we converged upon a usually vibrant intersection and Harrah's Casino. The casino, a billion-dollar

mammoth, is the only land-based casino in the state.

It was then, among the 15 gaming licenses available in the state, the only exception to the legislative wisdom decreeing that citizens and voters are safe from casinos only if they

are contained in floating riverboats. In

this rich cultural melting pot, decadence and religion have historically flourished side by side.

|

| Isle of Capri Casino - Lake Charles |

In traditions embracing Voodoo, historic red light districts, Bourbon Street strip clubs, European architecture, religious monuments and cathedrals, the contradiction was invisible and the exception seemed justified.

Our caravan came to an abrupt halt behind a line of similar truck-vehicle combinations that squirmed and disappeared into the concrete and glass canyon between The W and Windsor Court Hotels on one side and Harrah's on the other. By walking around the casino and through the canyon, we

confirmed that the snaking line of boats wrapped entirely around Harrah's, from Poydras, down

South Peters, then on Canal toward the River and then back toward the intersection where our folks rested.

We found fellow rescuers from other groups perched at the front of the line, primed and ready to go. Occasionally glancing skyward toward the dangling high voltage lines ripped from their standards, they anxiously awaited their instructions and information while milling around the area between the casino and the New Orleans International Trade Mart, now known as theWorld

Trade Center

I began to feel completely my 50 year old age, realizing that the gleaming local icons of my youth, that I remembered as vibrant new symbols of progress, were mostly re-named.

This old “Trade Mart”, along with the 33 level Plaza Tower on the edge of downtown, were the first two legitimate skyscrapers

built in New Orleans

|

| World Trade Center & Harrah's |

We found fellow rescuers from other groups perched at the front of the line, primed and ready to go. Occasionally glancing skyward toward the dangling high voltage lines ripped from their standards, they anxiously awaited their instructions and information while milling around the area between the casino and the New Orleans International Trade Mart, now known as the

|

| Plaza Tower |

“Hurry up and wait” was again the theme. Although we had only hit the road from Sulphur 4 - 5 hours earlier, it seemed like days. Now past

Confined to their wood-frame, island fortresses in this sea of familiar lake water mixed with gasoline, sewerage, garbage, animal feces and anything else previously located below the flood waters, we did not expect that those as yet unclaimed would want to cancel rescue efforts at dark and wait until morning to begin again.

Confined to their wood-frame, island fortresses in this sea of familiar lake water mixed with gasoline, sewerage, garbage, animal feces and anything else previously located below the flood waters, we did not expect that those as yet unclaimed would want to cancel rescue efforts at dark and wait until morning to begin again.

Around 6:00 o’clock p.m. , we had worked our way around

the casino to the point that we were ready to be deployed as a group to whatever assigned location awaited us.

During our wait, we exchanged stories and personal histories with our fellow rescuers and heard from locals and other boaters next to whom we had been thrown randomly by fate, timing and circumstance. The most vivid of these real life short stories was the one told by a Harrah’s employee who crossed our path while operating a forklift on

Before I could mentally process what bizarre and grotesque kind of physical harm could have befallen our fellow volunteers, he detailed stories of boats running over dead bodies in the water and similar grisly events. The realization at that moment, that his reference had been to psychological and not physical injuries provided no comfort, but rather heightened our growing anxiousness.

During the drive into the city, Sara and I had navigated our group from the lead vehicle. We pondered the unknown severity of the situation and speculated about what we might see in the still uncharted devastation left in Katrina’s wake. We were as uncertain of what we were getting into as we were determined to do it.

Ignorance is bliss.

We have encouraged each other to always be, together, mildly adventurous and open-minded. We are fortunate to have shared a variety of experiences together that we might not have otherwise ventured into alone. We did not speak of it, but on this day, we were both becoming increasingly aware that we had never done before, anything like that which we were about to do.

TO BE CONTINUED

No comments:

Post a Comment